Is German Debt Brake Change Politically Feasible?

The conventional wisdom is that a possible debt brake reform requires a constitutional majority. Is this really true? Why does it matter?

Hi there! In today’s (first) post I will:

explain what the debt brake is and how it works in practice,

describe one of its elements that can be altered so as to make more wiggle room for budget expenditures,

show what’s the effect of a possible reform.

The German debt brake came back to the spotlight a few weeks ago when the Constitutional Court had decided (in practice) that some off-budget expenditures have to return to the federal budget. As a consequence, the amount of net expenditures this year is going to be so large that the government has decided to suspend the debt brake for 2023 (that’s a fourth year in a row). What about 2024?

Well, in the face of gargantuan required investments for digitization and the green transformation over the next years, the best solution for Germany would be to reform the debt brake so as to allow the government to spend more (and thus run a higher deficit). However, this is unlikely to be politically feasible because such a profound reform would require a constitutional majority (two thirds) which the ruling coalition lacks. Nevertheless, the issue can be circumvented to some extent…

Design of the debt brake

As everyone knows, the German debt brake is designed to limit net budgetary expenditures, which exclude financial transactions. Of course, this mechanism can be deactivated in special situations (it was due to the pandemic and the war in Ukraine).

In normal times, the level of net spending is determined by two elements. The first is the structural deficit, which cannot exceed 0.35% of GDP. The second element is the cyclical component. In other words, the level of net spending is determined by both the structural and the cyclical components. It is not difficult to guess that the latter is aimed at increasing spending in recessionary periods and reducing it in periods of an economic expansion.

While a constitutional majority is required to change the structural component, the cyclical component has more room for maneuver. The size of cyclical spending is calculated on the basis of potential output, which in turn depends on a number of factors. A simple production function shows that potential growth can be decomposed into labor, capital and productivity. All of these factors must somehow be estimated and "put" into the model.

This is where the possibility of change arises, which is perhaps what German Finance Minister Lindner had in mind when he said in an interview on Sunday that he wanted to revise the calculation of the cyclical component1.

Three possible modifications of the cyclical component

Moving from NAWRU to full employment

The first proposed change is to abandon estimates of NAWRU (the structural unemployment rate at which wages don’t accelerate) in favor of full employment. Its definition could be approximated by adjusting the ordinary unemployment rate by the share of long-term unemployment. Starting from such a definition, it turns out that full employment defined this way would imply a much lower unemployment rate than the NAWRU estimate. Lower structural unemployment implies higher potential output.

Zeroing in on female labor activity

Women's participation in the labor force in Germany is significantly lower than that of men. The gap is much wider than in the Scandinavian countries, which have one of the lowest gaps. Meanwhile, a conservative assumption is made in Germany that female participation will remain stable over the budget projection horizon for the coming years. The gap has improved in the past, so this assumption can be considered conservative. Higher female participation implies higher potential output.

Increasing total hours worked

This is not an arbitrary assumption, but is based on Eurostat surveys. According to these, part-time workers chose this form of employment mainly because they couldn’t find full-time work or because they had to care for the elderly or children. However, if labor market conditions improved and investment in social infrastructure increased, the number of hours worked would be higher.

There were 5.6 million part-time workers in 2019. These workers indicated that they would be willing to work up to 10 hours more if possible. Therefore, the estimates of the number of hours worked component assumed two variants of +10 hours per worker and the more conservative +5 hours per worker. A higher number of hours worked means a higher potential product.

How would the fiscal room increase in the wake of these alterations?

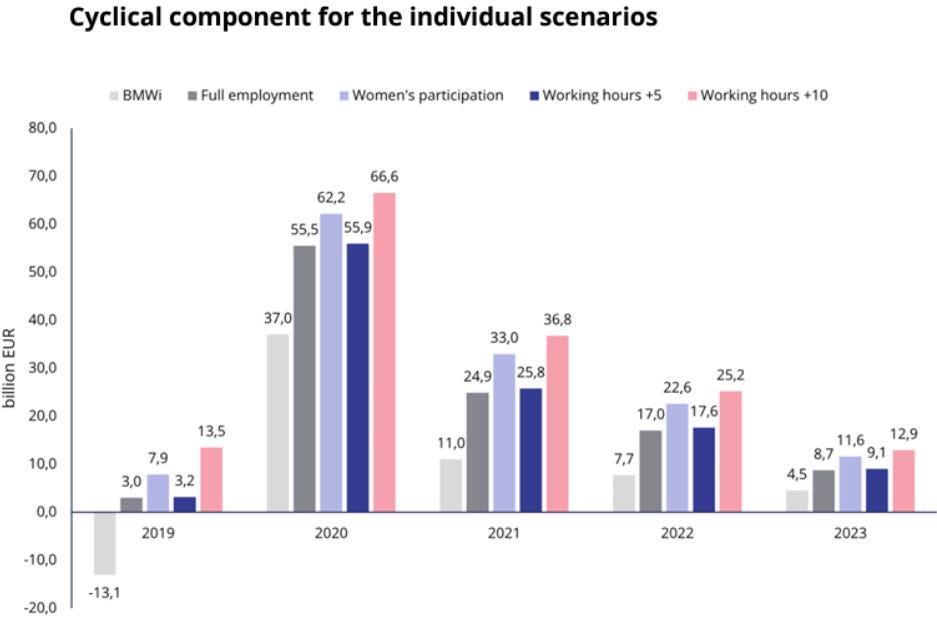

Estimates suggest that the largest gain would come from increasing hours worked by 10 hours per worker. The smallest effect would come from moving away from NAWRU estimates to full employment. In the chart, "BMWi" denotes the German Ministry of Economics and Energy's baseline scenario from 2020. For example, the economy overheated in 2019 (growth above potential output), resulting in a spending cut of more than €13 billion. Combined with the structural component, which increases spending by 0.35% of GDP, this would allow the government to increase spending by up to €2.5 billion. If potential output had been higher, it would have implied a smaller cut in cyclical spending.

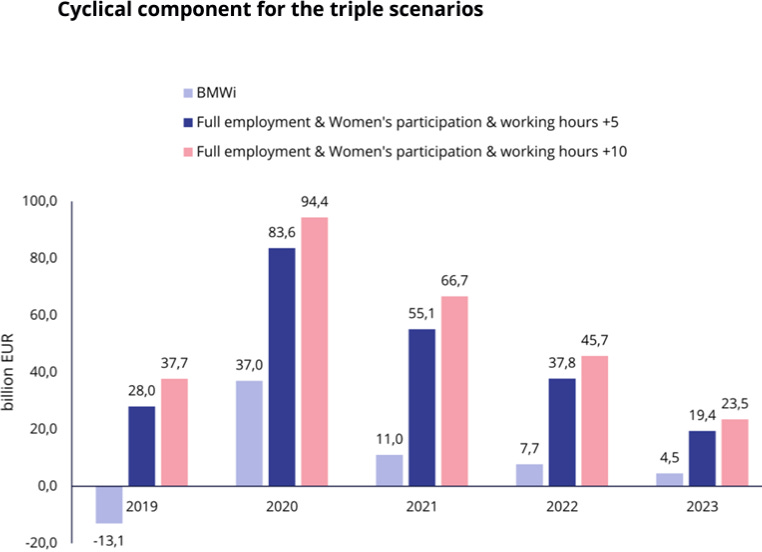

The combined effect produces much larger differences in implied spending. In 2020, for example, the cyclical increase in spending would have exceeded €94 billion, rather than €37 billion, if the abovementioned changes had been introduced.

If the government decides to move this way, the debt brake would be activated less often and the government would not have to look for an emergency to deactivate the mechanism. Note that the convergence of cyclical spending to zero is based on the model assumption that the output gap is closed in the final forecast period.

Conclusion

In practice, such a reform would make German fiscal policy less restrictive in difficult times. And here is the point. Looking at the current rate of economic growth, I think everyone would agree that a redesign of the debt brake would be desirable. After all, there is a lot of spending on the horizon related to energy transition or digitalization (where Germany lags well behind). In the longer term, the higher debt issuance resulting from the proposed reform would probably work out well for Germany.

Did you enjoy the piece? Please share this post and help me reach out to an ever-growing audience.

https://www.politico.eu/article/christian-lindner-germany-plans-partial-reform-of-its-debt-brake/