US Banks’ Free Lunch Set To End Soon

US banks are increasingly benefiting from a newly created Fed program. The facility is set to end as soon as March. Is this something to worry about?

Hi there! In today’s post I will:

discuss the Fed’s Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) in detail,

explain why BTFP has become more attractive recently,

demystify what BTFP’s termination could mean for the overall liquidity picture.

A short reminder at the beginning: BTFP was launched by the Fed in March 2023, when the whole saga of the regional banking crisis began (today I won't explain in detail what happened then, attention will be paid mainly to BTFP). A trigger of the crisis came from Silicon Valley Bank as well as Signature Bank, followed by First Republic. Given the fact that the bonds held by the banks were priced well below par at the time, the Fed decided to sweeten its toolkit by adding another option of raising liquidity - BTFP. Fast forward to the present and it turns out that BTFP is (probably) being used as part of an arbitrage. While the banks are obviously happy about this, it's likely to change soon.

Comparison of BTFP and Discount Window

The main advantage of the newly created facility is a way of valuing collateral. While a standard procedure (used, for example, in another liquidity backstop called Discount Window or Fed’s Standing Repo Facility1) is fair market valuation, BTFP differs significantly and values collateral at its face value. In practice, a bank holding a bond priced well below its par can raise much more money by using BTFP rather than Discount Window.

Other differences in favor of BTFP include a much longer term of up to 1 year, no haircuts applied to eligible collateral, and (currently) lower costs. The only (minor) disadvantage is that the pool of eligible collateral is strictly limited to what the Fed can buy in the open market (mostly Treasuries). In case of Discount Window, a borrower can pledge both highly liquid Treasuries and less liquid corporate bonds or even some types of loans. However, this disadvantage isn’t particularly burdensome given that fact that collateral is valued at par value in BTFP.

It's worth adding that the BTFP wasn’t originally intended to be a free lunch for banks and other players. Without any restrictions, a bank would buy a bond well below its face value, pledge that bond to the Fed, receive full face value, and invest the proceeds in risk-free assets. To prevent such a practice, the Fed said that collateral pledged under BTFP must have been owned by the borrower as of March 12, 2023.

In addition, the borrower using BTFP is not charged any additional fees over and above the actual rate: 1-year OIS + 10 bps. As a result, BTFP was very attractive at the beginning, and its attractiveness has only increased since then. Why is that? It all comes down to the difference between the cost of BTFP funding and a risk-free rate at which the borrower can invest the proceeds.

Interest rises along with potential profits

BTFP volume quickly jumped to around $80 billion and stayed there until May. Afterwards, we observed a steady increase towards $100 billion and then to around $110 billion. The situation was relatively stable until the end of November before something has changed. Namely, in December, BTFP volume increased by $21 billion to $136 billion - a new record high. What has been the driver this increase?

As I wrote earlier, interest of BTFP rises if a bank (or other borrower) can invest the proceeds in an attractive risk-free investment. In case of a bank, that investment is the interest rate paid by the Fed on reserves (IORB). Thus, when the IORB-BTFP spread rises, so does interest in taking a loan via BTFP. In short, a risk-free opportunity arises, so players start taking advantage of it.

In fact, that is exactly what has been happening lately. The aforementioned spread has risen above 50 bps, high enough to entice various players to step in. Why has this happened? The cost of BTFP funding is forward looking and tied to the 1-year OIS. As the Fed has become more dovish and market participants have begun to price in more rate cuts in 2024, market rates, like OIS, have moved lower. Voila, the arbitrage trade has become even more profitable. Importantly, even if market rates move higher again, the cost of outstanding BTFP funding won't change (no prepayments are likely unless the Fed starts cutting rates quickly, thereby driving IORB lower).

Do banks really need BTFP funding?

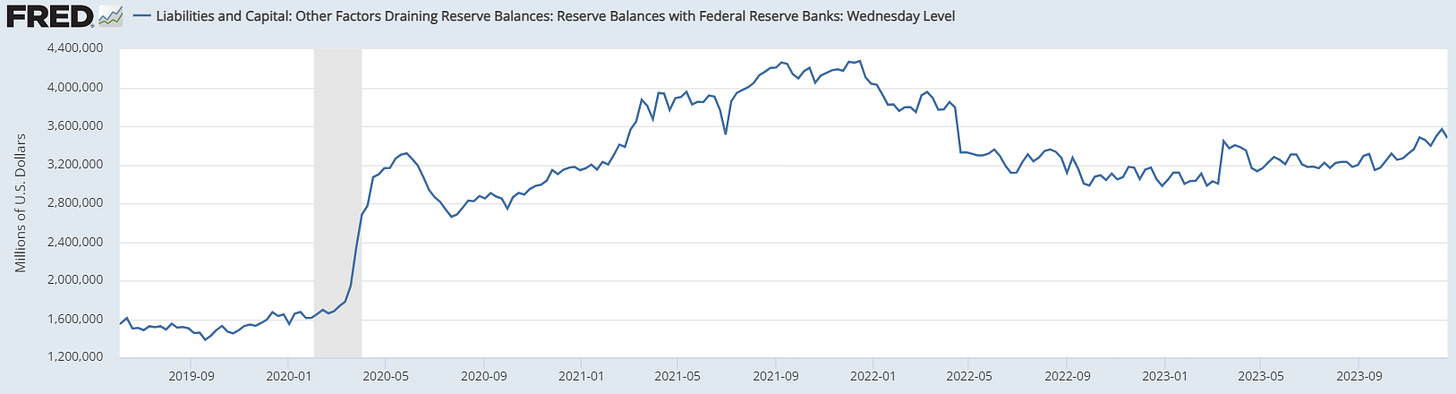

The simplest answer is probably no. First of all, the overall amount of reserve balances at the Fed is higher than it was in March 2023 (yes, I’m cognizant of the fact that the distribution of these reserves is far from equal). The major reason for this shift is the Fed’s Reverse Repo volume being redirected back to the banking system.

Second, the current environment is substantially different from the one we saw in the spring. What do I mean by that? When the banking crisis hit in March, there was a huge increase in funding, as evidenced by a surge of Discount Window usage. This facility then acted as the first backstop offered by the Fed to market participants, which subsequently was supplemented with BTFP.

However, the Fed’s balance sheet swelled at that time for another reason. Namely, in order to guarantee all of the deposits held by insolvent regional banks, the Fed had to backstop the FDIC, which at the time didn’t have enough money to do so on its own (the amount of all deposits held by these banks far outstripped the overall capital at the FDIC’s disposal). It had to be reflected in the balance sheet. As a result, the Fed created a new line called “other credit extensions” adding the annotation:

Includes outstanding loans to depository institutions that were subsequently placed into Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) receivership, including depository institutions established by the FDIC. The Federal Reserve Banks' loans to these depository institutions are secured by pledged collateral and the FDIC provides repayment guarantees.

Thus, this position, along with BTFP and Discount Window, was behind the increase of the Fed’s balance sheet at that time. After a sudden spike in Discount Window usage, there was a steady decline followed by a steep decrease. What caused this decline? The Fed has an answer2:

On May 1, 2023, the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation closed First Republic Bank and appointed the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) as receiver. For purposes of the H.4.1, the Federal Reserve's outstanding lending to First Republic Bank at the Discount Window and through the Bank Term Funding Program are now reflected in table 1 as "Other credit extensions". The outstanding loans are being repaid from assets left behind in the receivership, proceeds of the purchase and assumption agreement between the FDIC and JPMorgan Chase Bank, National Association, and pursuant to an FDIC guarantee.

What did it mean? The increase in Discount Window usage stemmed almost solely from First Republic. We haven’t observed any notable increase in Discount Window usage since then. At the same time, the position “other credit extensions” started declining as the assets of the insolvent banks were sold off. As one could have expected, the position finally dropped to zero in December. To sum up, I suppose that a large part of BTFP usage is purely profit-driven rather than liquidity-driven.

What will happen with BTFP?

The program is set to expire after March 11, 2024 unless the Fed extends it. Can the Fed do so? The Fed can always do this, but why this time around? When setting up BTFP in March 2023 the Fed wrote3:

Recent events have resulted in stress to certain U.S. banks. The Board determined that unusual and exigent circumstances existed and approved the establishment of the BTFP.

What do these conditions look like today? Well, there’s no doubt that they are much more benign4. Even as the Fed is proceeding with QT, the amount of money coming back from RRP is more than offsetting the QT’s impact. That’s why the amount of reserve balances hasn’t declined yet. In my view, the Fed will either let BTFP expire as scheduled or keep the option alive with much less favorable terms. I’d would opt for the former solution.

What could it mean? If all BTFP usage is purely profit-driven, then nothing is going to happen (the Fed’s balance sheet is going to shrink when remaining loans are paid off). If some of BTFP usage is liquidity-driven, then some uptick in either Discount Window or Standing Repo Facility cannot be excluded5. However, I don’t find enough reasons to believe that BTFP’s termination is going to send a shockwave across markets.

And again, both Discount Window and SRF are designed to provide cash to borrowers on an as-needed basis (when they can't access cash in the private repo market), thus preventing private repo market rates from rising above the ceiling set by the Fed. In this way, the Fed is able to keep market rates within a desired corridor. For this reason, the use of either facility should be treated as a normal procedure under the ample reserves regime. Looking ahead, I expect these facilities to be used more frequently next year as the dollar supply finally begins to shrink.

Did you enjoy the piece? Please share this post and help me reach out to an ever-growing audience.

I plan to make a separate post on various interest rates prevailing in the US, stay tuned.

https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h41/20230504/

https://www.federalreserve.gov/publications/files/13-3-report-btfp-20230316.pdf

As far as regional banks are concerned, there's some risk on the horizon due to a number of regulatory proposals that are likely to have a negative impact on these types of institutions (if the regulations are enacted as proposed a few months ago).

I do expect that SFR usage might start rising somewhere in 2024 when the RRP volume is drawn out altogether and the Fed keeps proceeding with QT.