Understanding Long-Run Changes In Global Macro

In global macro, it's outstandingly important not miss the forest for the trees. That's why I've decided to bundle all my structural macro views into one concise post.

Every day and everybody is littered with an endless amount of information. The same concerns financial news. However, sometimes if you’re very close to a given topic, you cannot take a broader look, which in my view is necessary, at least from time to time. The current macro developments, and what’s to come in the future, seem to require such a deep dive into some assumptions/structural views. I’m not gonna overwhelm you with tons of pages, but instead I’ll try to be as brief as possible.

A short remark before we move forward: the points presented below focus mainly on the US, given data availability and the importance of this economy in the world.

1. More volatility in macro data

The pandemic showed that supply chains can become unstable quite quickly. This instability is likely to prevail in the years to come, driven by the green transition and related shocks to commodity prices, with important consequences for financial markets (see point 9). On top of that, we are developing AI technology, which will require a significant amount of energy. That’s why I think that the US can become a net energy importer again after becoming a net exporter in 20191. Moreover, if more and more companies start deploying AI-driven tools in their routine management activities, it could speed up the pace of prices adjustments for various reasons.

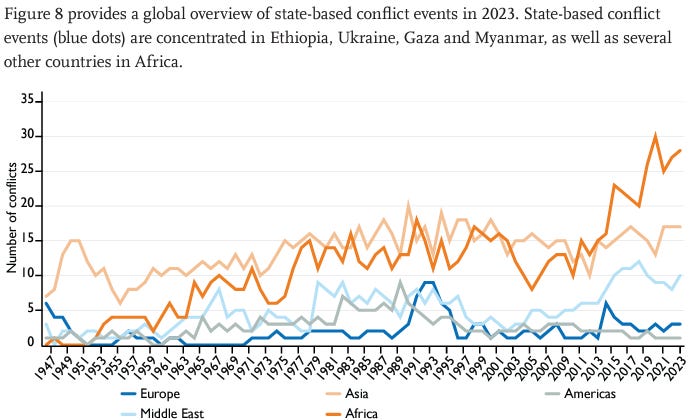

An unstable geopolitical environment can also contribute to increased volatility in macro releases. The number of wars and conflicts has increased notably in recent years, and we may feel it almost every day when we read various articles. Furthermore, Africa has become the continent experiencing the largest rise of this type of events. Why do I mention it? Africa is home to plentiful reserves of critical minerals necessary to carry out the green transition. For instance, the Democratic Republic of the Congo accounts for roughly 50% of the global cobalt output, which is required to make batteries to EVs.

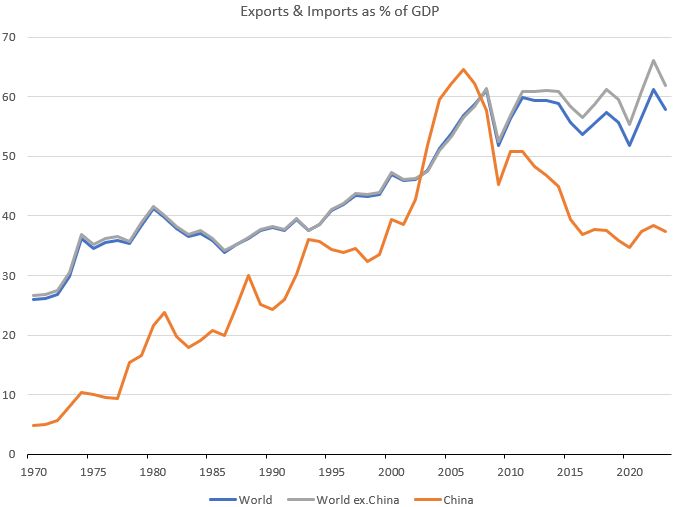

Finally, a deglobalization trend seems to be on the rise for some time now, and the events like the pandemic may have only increased the desire to shorten supply chains. To be frank, globalization stopped rising right after the GFC, driven to some extent by China. However, even without China, we’ve been moving sideways for years. If the deglobalization trend unfolds, it could mean more volatile economic cycles.

2. Frequent but shallower recessions

Following the GFC, we all learnt that central banks became serious when dealing with economic slowdowns. Moreover, they remain very attentive to risks coming from the banking sector, as we saw in the US in the spring of 2023. Thus, I assume that central banks will stand ready to respond quickly and forcefully to this kind of events. Therefore, I wouldn’t be afraid of recessions brought about by financial markets. Instead, recessions are more likely to come from the real economy (see point 1). If so, they may become a larger problem for the real economy rather than financial markets.

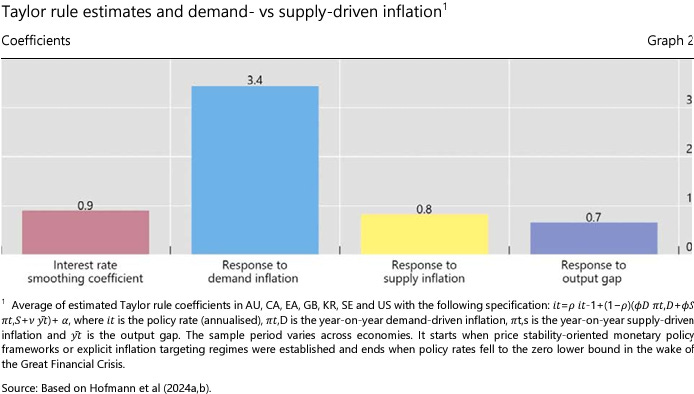

Moreover, in the past, central banks were, on average, more than threefold more responsive to demand-driven rather than supply-driven inflation. I think that’s going to change in the future. Why?

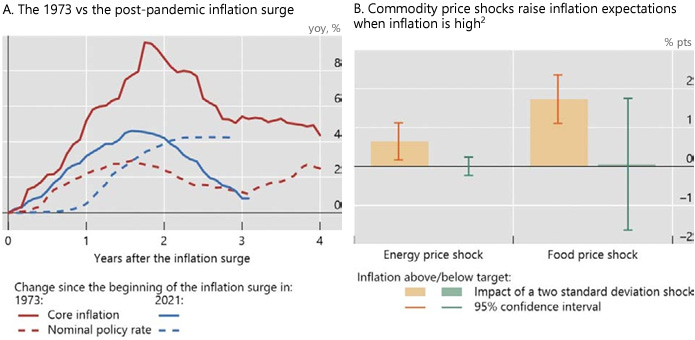

Well, the post-COVID monetary policy response proved much stronger and more durable than in the 1970’. As a result, post-COVID inflation subsided earlier. I believe that central banks will follow this way of thinking because of:

more frequent supply shocks (see point 1),

tighter labor markets coupled with deglobalization trends (the steeper Philips curve),

elevated inflation, leading to the increased likelihood of second-round effects.

According to the cited BIS report, if inflation is above the target and a supply shock hits, a CPI increase leads to a rise in inflation expectations. And I believe inflation to be somewhat elevated compared to the targets in the years to come (see point 3).

3. Elevated inflation

In short, I believe that a 2% inflation target is likely to be seen like a floor than a ceiling. We’ve already seen this with the Fed cutting rates when both inflation and wage growth are above their pre-pandemic levels.

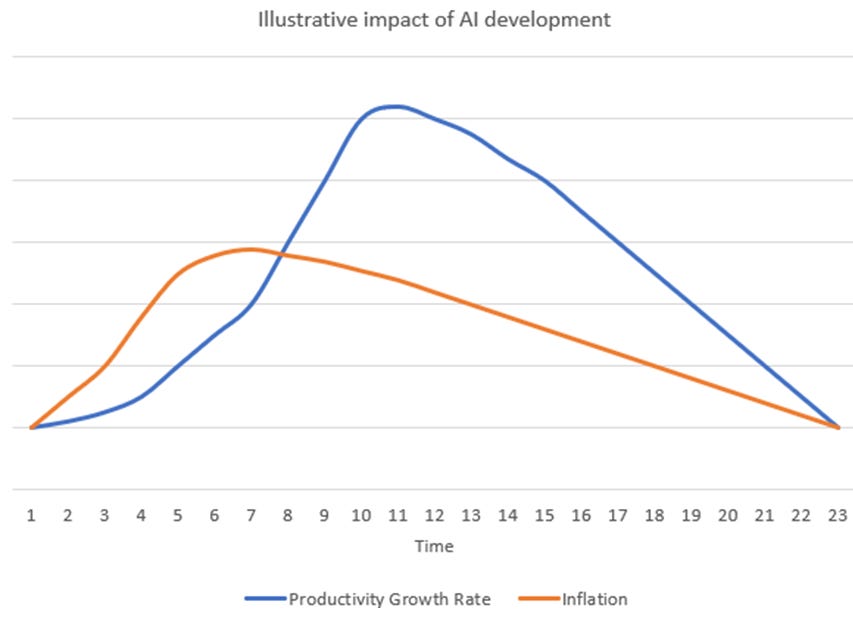

This view is also driven by the AI revolution. At first, it will require huge investment, which is likely to produce higher inflation in the short-term. So, you’ll see first that AI will boost demand, and only then the supply side of the economy translating to higher productivity growth (see point 4). To be honest, this huge AI-driven investment is already happening.

4. Labor productivity to be higher for longer

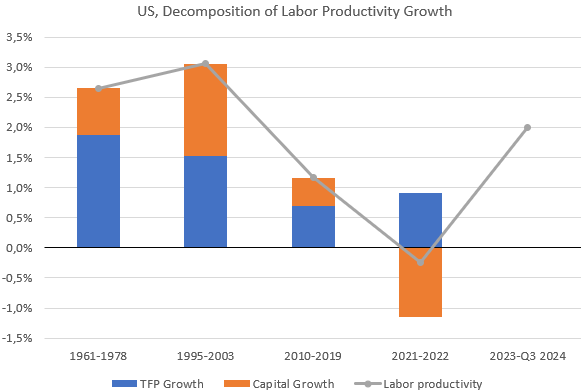

We’ve already seen a higher growth rate of labor productivity lately. I believe that increased efficiency in manufacturing, brought about by the green transition, will boost TFP growth. On top of that, given the gargantuan amount of investment needed in the years to come (not only AI-driven), the amount of capital might increase too, also contributing positively to higher labor productivity growth.

How high can we go? Looking through the previous productivity cycles, we may conclude that a 3% annualized growth rate isn’t something unattainable at all. During the ICT revolution, we reached such a level for almost a decade. After the 2010-2019 “lost decade”, when productivity growth was often the lowest since the industrial revolution and a period of pandemic disruption, we’ve been experiencing a sharp acceleration. I firmly believe that the AI revolution won't be any weaker than the ICT revolution in this respect.

5. Higher potential GDP growth

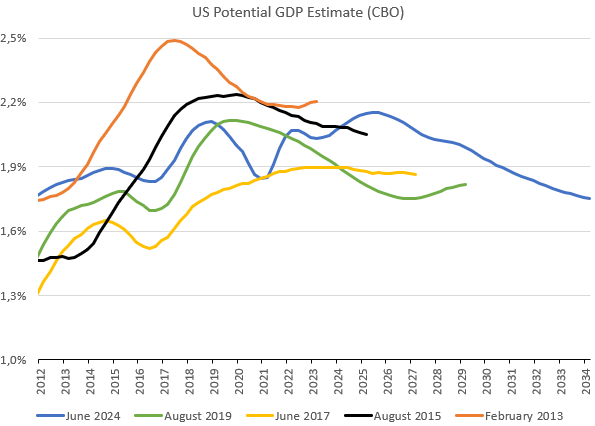

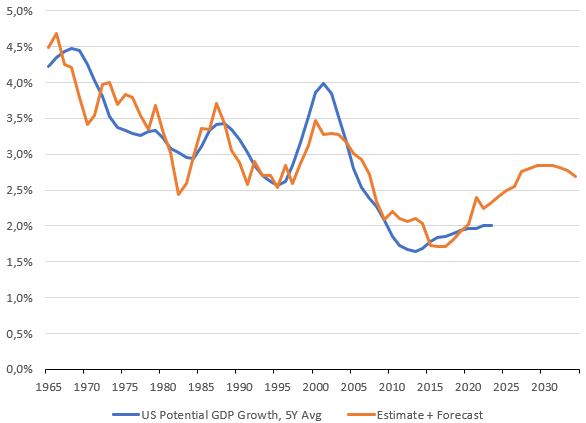

If we experience labor productivity rising faster, then potential GDP growth will also see a boost. In fact, it may be already happening2. Meanwhile, the CBO doesn’t think so, at least for the time being. In the previous years, the CBO has continuously revised potential growth down, and its newest estimate from mid-2024 isn’t any different. It sees this growth only slightly and briefly above 2%, and then a slide well below this level is envisaged.

I’m more optimistic here, and I think we may experience growth even above 2.5% over the next decade or so. Assuming a 0.7% annualized growth rate of labor force (the CBO estimate) and a TFP growth rate at 1.5% (the level seen during the ICT revolution), I’ve arrived at the result shown below. Note that the blue line represents the CBO estimate.

6. R* to be higher

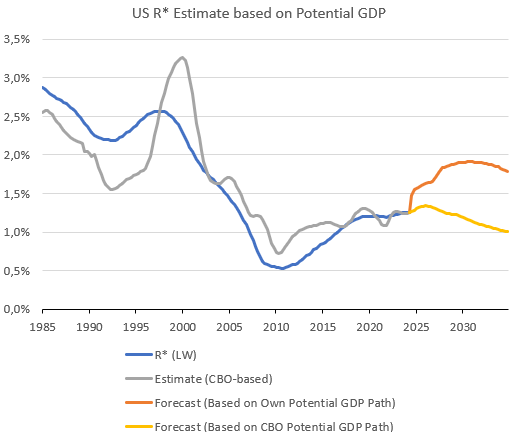

I’ve written several times that in my view R* (the real short-term equilibrium rate) will be higher in the next decade or so. Note that geopolitical events, wars and other disasters tend to reverse a prevailing trend in R*3. That’s why I still believe the Fed’s own estimate of the neutral rate at 3% is too low4. It’s obviously based on the assumption that labor productivity will be growing faster than before (see point 4).

My guess is that the Fed’s neutral rate will be closer to 3.5-4% for the years to come, which would translate into 1.5-2% in terms of R*. Based on the assumed potential GDP growth in the coming years (see point 5), I’ve arrived at the similar estimate. Note that the CBO doesn’t seem to believe in any rise in R*.

7. Reflationary fiscal policy

As I’ve written before, the 2010-2019 decade was lost due to low productivity growth, fiscal austerity, widespread deleveraging of the global economy and discouraged companies which didn’t invest. However, fiscal policy turned more expansionary during the pandemic (the inflection point), something that central banks had been calling for. I think this thinking will prevail going forward. Needless to say, fiscal policy will be reflationary (nominal growth will be higher), hence govts are unlikely to face huge difficulties. Of course, bond vigilantes might occur from time to time either way.

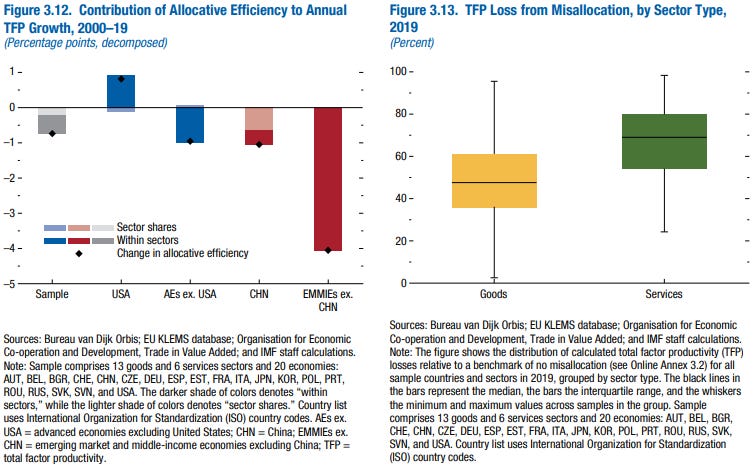

8. Better allocation of resources

It should be driven be higher interest rates, and it itself may increase TFP growth. The IMF research shows that the US, unlike other regions, saw a positive impact of allocative efficiency on TFP growth during the previous decade. It means that the US had, on average, appropriate allocation of labor and capital, while others didn’t.

Note that China saw expanding sectors already facing sizeable capital/labor misallocations. That’s why it took a hit from allocative efficiency on TFP growth. By the way, the weak outcome may also reflect huge subsidies the govt channeled to SOEs with weak productivity at the time. Finally, given that fact that the hit to TFP growth from inappropriate allocation of resources is larger in the services sector, China may see a continued negative effect of this factor on TFP growth as it expands this sector in the coming years (it’s basically doing so).

9. Markets

Bond yields are likely to stay well above the pre-pandemic levels owing to the higher R* itself and huge budget deficits.

The higher (and volatile) interest rate environment is also likely to be connected with a higher term premium, which in turn should lead to positive stock-bond correlation. I've already written the extensive post on this topic, so I won't repeat myself.

The stock market ought to benefit from reflationary policy coupled with quicker productivity growth (you can read more about it here). Higher rates shouldn't hurt equities in this environment, unless we see abrupt moves to the upside (the pace of changes is what investors should keep a close eye on).

Did you enjoy the piece? Please share this post and help me reach out to an ever-growing audience.

Would you like to share your opinion on the subject? Don't hesitate to leave a comment.

https://www.eia.gov/energyexplained/us-energy-facts/imports-and-exports.php

https://x.com/Insider_FX/status/1846985345566482828

https://bankunderground.co.uk/2017/11/06/guest-post-global-real-interest-rates-since-1311-renaissance-roots-and-rapid-reversals/

https://x.com/Insider_FX/status/1867935193463763004