When Will Fed Stop QT?

It's undoubtedly the $64k dollar question. Even if it's a tough task to get at least an approximate date, I think it's worth it.

Hi there! In today’s post I will:

try to identify a certain level of reserves that the Fed probably doesn't want to fall below,

present a bunch of forecasts for key components of the Fed's balance sheet,

show what might convince the Fed to wait longer before implementing QT tapering.

Answering the question in the title isn’t a trivial task and it requires a lot of assumptions. As such, there’s huge uncertainty around the estimates I’m presenting in this article. But I find these estimates better than none to guide market participants what and when to expect going forward. In the previous post I wrote why the Fed should consider implementing QT tapering before long. Today, I’m gonna answer when one should expect it to happen.

What are we aiming for?

The starting point for this analysis must focus on a reference point against which we can then benchmark. I am referring to the so-called Lowest Comfortable Level of Reserves (LCoR). If you knew where that point was, you could easily determine when the Fed should start QT tapering. The problem is that nobody really knows, including the Fed. That doesn't mean we can't try to estimate that point. I have decided to look at two possible candidates, although both approaches are relative. Why? The answer is simple: the demand for reserves increases with the size of the economy and the banking sector as a whole.

So, the first approach is the ratio of bank reserves (cash assets) to GDP. On top of that, I’ve also included the amount of cash placed at the Fed (the ON RRP) because it’s equivalent to reserves (once reserves run out, then the demand for funding in the private repo market increases and the ON RRP declines). As a result, the most important line here is the gray one, which combines reserves and RRP volumes. Taking this measure as a proxy for the LCoR, one can identify that this level could stand at around 7%. When the gray line fell below this point in September 2019, then SOFR spiked. That was when the Fed decided to boost liquidity by buying a lot of T-bills from the market.

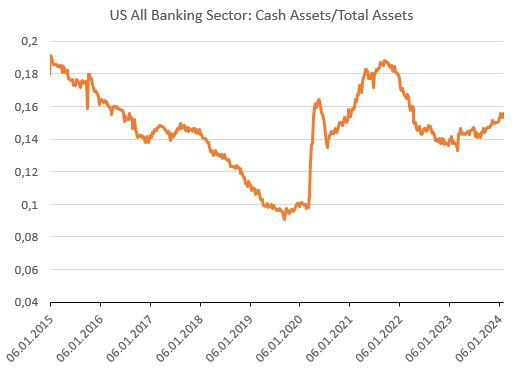

The second approach is the ratio of banks’ cash assets to total assets. It’s basically reserves to total assets of the banking sector. I prefer this approach for two reasons. Firstly, RRP volumes have shrunk significantly of late suggesting that before long it’ll no longer help offset the QT impact on reserves. Secondly, Powell told as at his latest press conference that there was no need for RRP to go zero before tapering. In September 2019, the ratio of reserves to total commercial bank assets was 9%. And this is the point I treat like the LCoR, though the Fed doesn’t have to think the same. What’s more, it’s even more likely that it wants to be more cautious this time around and assume even a higher number. So, let’s say that we know where the LCoR is. Now, it’s time to project when it might be hit.

Please note that a number of assumptions have been made in the graphs below. So don't take these estimates for granted.

Fed’s assets

I’ve identified four major components comprising of ~99% of the Fed’s total assets. I'll briefly describe the methodology used to arrive at the estimates shown in the chart below.

BTFP - the Fed changed the terms of BTFP funding last month, thus it’s no longer profitable to get BTFP funding and place those funds back to the Fed. I assumed that there will be no new demand for this funding which is set to expire on March 11. Given the fact that the new terms don’t apply for existing loans, I don’t assume that banks will be eager to pay them back earlier. Therefore, I assume that the existing loans will be paid back when they simply mature (the loan cannot be longer than 1 year).

Treasuries - since the start of the QT the Fed has been able to keep the pace of reducing Treasury holdings at $60 billion per month (on average). I expect this pace to continue.

MBS - the Fed’s self-imposed cap for monthly reductions of MBS holdings was set at $35 billion. However, the maturity profile wasn’t high enough to reach this point. Therefore, the Fed has been decreasing MBS holdings at the pace of ~$17 billion per month. I’ve chosen to extrapolate this pace.

Unamortized premiums - this position reflects the difference between the purchase price and the face value of the securities that has not been amortized. As long as the Fed doesn't start QE again, nothing should happen here.

Fed’s liabilities

In case of the Fed’s liabilities, I also chose four of them, which together account for approximately 53% of total liabilities. Note that reserves, the Fed’s liability, constitute the difference between the total assets and the total liabilities ex-reserves.

Currency - I assumed the amount of currency will be rising in line with the 2010-2019 trend. It was the period of steady increase before the pandemic struck.

TGA or Treasury General Account - it seems one of the hardest components of the Fed’s liabilities to project. This is because the TGA depends on a lot of other things like tax receipts, the pace of outlays, the pace of Treasury issuance or the Treasury’s desire to keep a certain amount of cash as a cushion. I expect some seasonal decline in Q1 following a seasonal increase in Q2 (tax receipts). From Q3 onwards, I assume a steady decline toward $550 billion (approximately the average value between 2022 and 2023).

ON RRP - the assumption is a further decline of RRP volumes in Q1 on the back of continued heavy T-bills issuance. The pace of the drawdown is expected to slow a bit in Q2 and the overall balance is anticipated to be at 0 by June 2024. Let me note that I expect that RRP volumes will be drained even as the Treasury stops net T-bill issuance in Q2. This is because I expect a growing demand for funding due to sizeable issuance of coupons in Q2.

Foreign repo - along with lower rates, I assume foreign repo volumes to decline gradually toward $240 billion and stay there (this is the average volume between 2016 and 2019).

All of these estimates bring me to the implied path for reserves presented above. In short, after a short-lived (and small) increase driven by the ON RRP drawdown, reserves are projected to decline gradually as the Fed continues QT.

When might the LCoR be hit?

Before we answer the question, we have to project the total commercial bank assets. I’ve done it by extrapolating the 2010-2019 trend, when the assets were growing almost linearly.

Having known how banks’ assets will evolve, we may project the ratio of reserves to banks' total assets over the coming months. Under all of these assumptions, the ratio hits the 9% threshold in Q4 2025. However, the level of 13% - when the regional banking crisis burst in the spring of 2023 - is projected to be reached in Q1 2025.

So, can the Fed continue the QT process? On the face of it, the simple answer would be yes. Reality is more nuanced, though.

First of all, any change in the balance sheet strategy takes time. That’s why Powell already let us know that in-depth discussions on QT tapering will be held in March. Even if the Fed agrees to QT tapering “now”, its implementation is unlikely to come into force until the end of H1 2024.

Secondly, QT tapering doesn’t mean reserves stop falling from now on. It simply means the slower pace of this process. Keep in mind that when the 13% threshold is reached, then the Fed’s balance sheet will have to grow gradually to keep it unchanged. So, it seems quite prudent to start QT tapering already in Q3 and do it step by step.

Finally, we actually don’t really know what the Fed thinks of the LCoR - where it basically stands. So, one would expect the Fed can be much more conservative this time around than it was the case in September 2019. By starting QT tapering in Q3, and communicating the process appropriately, the Fed might gain some elasticity in terms of future changes based on how market conditions evolve. That’s my base case scenario, even as I think that reserves are likely to remain comfortably high until Q4.

Can QT tapering be postponed?

There’s one thing that can put off QT tapering for some time. Such a scenario would be possible once the Fed truly believes that there’s no longer a stigma attached to the discount window. While it crucial going forward, it’s rather unlikely it’ll be done in the near future. As a consequence, the Fed can think that banks are likely to keep the relatively high amount of reserves due to precautionary reasons. It’s worth noticing here that the Swedish Riksbank has already attempted to sterilize all SEK excess liquidity, but without full success. Instead, domestic banks preferred to keep ~20% of excess reserves despite the fact that they pay a lower rate of remuneration1.

However, if the stigma is truly removed in the future, the Fed will afford to keep QT in place for as long as possible.

That’s something I think is remarkably important for the stock market performance in the years to come. It’ll be another topic I’m gonna cover. Stay tuned!

Did you enjoy the piece? Please share this post and help me reach out to an ever-growing audience.

https://www.ecb.europa.eu/press/key/date/2023/html/ecb.sp230327_1~fe4adb3e9b.en.html