Why It's So Important To Remove Discount Window Stigma?

US regulators may force banks to tap the Fed's discount window. It could be a very prudent step in order to remove the stigma and avoid future flare-ups in money market rates.

Hi there! In today’s post I will:

sketch out a plan of US regulators regarding the discount window,

explain why removing the stigma is important for money market rates,

show what the Fed can learn from the Bank of England in this regard.

Each central bank has its own emergency backstops to provide eligible market participants with liquidity if they’re unable to tap it elsewhere. However, resorting to any central bank’s programs can come with the so-called stigma, i.e. some market participants aren’t credible enough to get funding in the private repo market. For this reason, financial institutions tend to refrain from borrowing from the Fed even if there’s a need to do so. Therefore, the Fed has already made some steps toward de-stigmatizing the discount window, but more needs to be done. This is especially true as we are operating in the supply-driven floor system in the US which can produce undesired spikes in money market rates from time to time. What’s on the table? What can the Fed learn from the Bank of England? Let’s dig into the topic!

What’s the plan outlined by the US regulators?

The US regulators have recently come up with the plan to require that commercial banks tap the Fed’s discount window at least once a year so as to reduce (or hopefully remove) the stigma and ensure that all eligible borrowers have all required systems set up to use the emergency liquidity funding if needed.

According to the Bloomberg article1, banks would have to borrow whatever amount they want, just to ensure that they can access the facility in troubled times. On top of that, the regulators are reportedly mulling over lowering the cost of borrowing from the discount window.

The Fed has already made an important step

In practice, the Fed has currently two emergency facilities in place. The first one is the discount window, and the second one is the so-called Standing Repo Facility (SRF). Today, I’m not going to cover the latter, but I plan a post regarding the most important rates in the US financial system. So, no worries, the topic will be covered in detail in the future.

Let’s go back to the discount window now. If someone is troubled and unable to borrow from private financial players, then it can always go to the Fed’s discount window. Of course, it concerns only eligible borrowers which are composed primarily of depository institutions in sound financial conditions. The SRF offers loans to a wider set of counterparties. A loan from the Fed must obviously be collateralized by a set of eligible collateral. What stands out, in case of the discount window’s loan, is the fact that there is a number of eligible banks’ assets which may be pledged. This stands in stark contrast to the SRF where only Treasuries and agency securities are accepted.

The Fed says that the below assets are most commonly pledged to secure discount window loans2:

Commercial, industrial, or agricultural loans

Consumer loans

Residential and commercial real estate loans

Corporate bonds and money market instruments

Obligations of U.S. government agencies and government-sponsored enterprises

Asset-backed securities

Collateralized mortgage obligations

U.S. Treasury obligations

State or political subdivision obligations

Needless to say that different haircuts apply to specific assets. In short, the riskier asset, the less money can be raised. The full list of margins for various securities can be found on the Fed’s discount window website3.

The last important thing concerns the cost and term of discount window loans. Namely, an institution can receive a loan for up to 90 days at the rate equal to the upper range of the Fed funds rate. To sum up, the discount window has two advantages over the SRF: a type of assets pledged as collateral and the longer term of advances (under the SRF funding can be accessed most often overnight, though term repos are also available). On the other hand, the discount window has one disadvantage: it’s a loan not a repo transaction as the SRF is, hence it entails the abovementioned stigma.

What does the discount window stigma come from? Well, discount window borrowing remains undisclosed for 2 years, hence it seems ridiculous to fear of it. However, market participants can always sniff out who has drawn down the loan from the Fed and then some problems for this specific institution might unfold (it may not find counterparties to deal with them). Moreover, the Richmond Fed paper4 found that:

[…] some discount window borrowers pay higher rates in the market than those paid by banks that do not borrow from the discount window […] some banks are willing to pay higher interest rates in the market than the ones they would be able to obtain at the discount window, thus avoiding the discount window altogether.

On that account, it seems to be understandable that some counterparties might avoid this facility. Thus, the Fed needs to get rid of that as soon as possible.

It made a big step in March 2020, when the pandemic rattled the markets, and equalized the cost of discount window loans with the SRF rate (the upper range of the Fed funds rate). Before 2010, the spread was 25bps and then it was even increased to 50bps. By removing the penalty rate of discount window loans, the Fed wanted to convince market participants that resorting to the facility should be treated like business-as-usual. Not everybody got it, though.

Nobody should be surprised that the Fed needed to launch the SRF when the repo crisis burst in September 2019. As the chart above shows, the discount window usage (Primary Credit) was well below the SRF’s volume. The situation looked differently during the regional banking crisis last year, though the BTFP may have played a role too. The stigma is arguably still there.

Why removing the stigma is important these days?

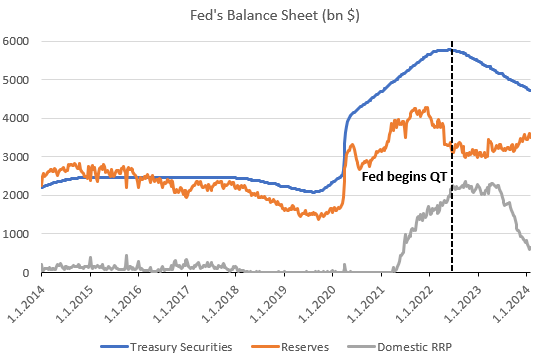

The Fed is still proceeding with its QT process, though it has had a limited impact on USD liquidity thus far. A steady decline in the ON RRP volume, where mainly money market funds park cash at the Fed, explains why the reserves haven’t decreased as of yet. How has it happened?

The US Treasury is primarily responsible for such a move. When the Fed’s balance sheet began shrinking, the Treasury needed to issue new Treasuries. Unlike the previous situation, when the Fed bought a tone of them, the new issuance needed to be purchased by other players. When the debt limit saga came to an end, the Treasury decided to issue bills… a lot of bills. It led to the higher yield which finally drew attention of money market funds. The ON RRP volume began to fall, thus cash started to come back to the banking system. That’s it.

Note that it was solely in the hands of the Treasury which tenor to issue. If the Treasury had chose to issue notes and bonds with maturity well above 1 year, then the QT process would have started lowering reserves at its very beginning (though some decline in the RRP volume would have occurred over time due to the rising demand for funding in the private repo market).

Nonetheless, the ON RRP volume will finally be emptied and then the amount of dollars in the system will start falling at the pace determined by the Fed’s QT. If it happens, then we’ll ultimately begin a journey towards the so-called LCLoR (the Lowest Comfortable Level of Reserves). To avoid flare-ups in money market rates5, it’s in the Fed’s interest to remove the discount window stigma and thereby convince eligible counterparties to borrow quickly if needed. Keep it mind that the amount of reserves isn’t distributed equally among depository institutions6, hence when reserves suddenly become scarce, rates can spike immediately.

What can the Fed learn from the BoE?

After the Great Financial Crisis, we entered the ample reserves regime, albeit there are two different types of it. The first one is a supply-driven floor system operated by the Fed, while the second one is a demand-driven floor system which has been adopted by the BoE. The British variant allows banks to determine for themselves the adequate level of liquidity they need.

To make sure that the amount of GBP liquidity remains adequate, hence money market rates remain in the desired corridor, the BoE chose to introduce the Short-Term Repo (STR)7. These are weekly operations at the cost equal to the BoE’s base rate, so no penalty rate applies. Thus, each week the BoE offers unlimited liquidity. Below you can study an illustrative example of how STR operations work as the BoE's balance sheet shrinks.

What did the BoE do to convince market participants to use STR operations on a regular basis without fear of the stigma? Firstly, no penalty rate applies. Secondly, the BoE told its counterparties that STR transactions are the same as any other transactions carried out without the involvement of the central bank. Thirdly, the Prudential Regulation Authority (PRA) made it clear that it will treat STR transactions as routine participation by the institution in the money market.

The Fed may tick the first point, but it still lacks the two remaining ones. By forcing eligible borrowers to set up all necessary resources and tap the discount window once a year to test their technical capacity, it could make us closer to remove the stigma once and for all. If it's done right, we can avoid future flare-ups in money market rates and all the knock-on effects for other markets. That's why I think it's so important to remove the discount window stigma.

Did you enjoy the piece? Please share this post and help me reach out to an ever-growing audience.

https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-01-18/us-preps-rule-to-push-more-banks-to-use-the-fed-discount-window

https://www.frbdiscountwindow.org/Pages/General-Information/The-Discount-Window#pledging

https://www.frbdiscountwindow.org/Pages/Collateral/collateral_valuation

https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/economic_brief/2020/eb_20-04

I’m gonna write about this topic in detail in the next post.

https://www.ft.com/content/09a77c41-169c-4b3d-898d-041045d1dbde

https://www.bankofengland.co.uk/markets/bank-of-england-market-operations-guide/our-tools